Anatomy of a Couch Potato

An Exploration into Traditional Movement Therapy

couch potato

noun

1. : a lazy and inactive person

especially : one who spends a great deal of time watching television

Before I dive into this, I need to make a statement: I have nothing against potatoes. In fact, on most days, I quite like them, especially mashed. So to all of the farmers who protested the removal of this phase from the dictionary citing that its inherently negative connotations are harmful to the image of the potato, please do not take offence. Any media is better than no media, right? Ok, moving on…

The potato really isn’t the best imagery to make my point anyhow. I researched the life cycle of the potato, it looks like this:

Nothing unusual here, starts out as a cute little potato, sprouts, grows, blossoms pretty little flowers, then dries up and dies. Just like people! (Minus the flowers.) It’s the same growth and decline process that most living things go through. And so, potatoes don’t really offer any unique insight into the nature of movement. Quite the opposite… They fit right in! (There you go farmers. Chill).

Let’s dig a bit deeper, like say, the first line of Neo-confucian scholar Zhou Dunyi’s (1017-73 CE) famous essay, Discussing the Taiji Diagram (Tài jí tú shuō 太极图说):

无极而太极。太极动而生阳,动极而静;静而生阴,静极复动。

Wuji (non-definedness/singularity) becomes Taiji (somethingness/polarity), Taiji moves and gives birth to Yang, at the extreme of movement is stillness, stillness gives birth to Yin, the extreme of stillness then returns to movement.

Now this is something I can (metaphorically) sink my teeth into! This essay was quite influential at the time, and moving forward, established a solid and practical foundation for Taiji philosophy. It embodied a very simple premise: Taiji is expressed as Yin and Yang which fundamentally represents movement and stillness. Movement is the Yang part. Stillness is the Yin part. This is a solid basis for understanding the nature of movement. However, we do need to dig a little deeper still. Bear with me.

In the example of Taiji, Yin does not represent true stillness. In fact both Yin and Yang together, as one, represent the whole of movement. The most important aspect regarding Yin and Yang is that there is a relationship between them that allows for movement. Yin is the passive aspect of movement, Yang is the active aspect of movement. Still confused? Don’t be, I’ll give you some examples.

Below, you can see a picture of me flexing my biceps.

For me to be able to do this, my biceps brachii, brachioradialis, and brachialis need to contract, while my triceps needs to relax. If my triceps doesn’t relax, flexion will not occur. So there you have it, for the agonist (flexing muscle group) to create motion through contraction, the antagonist (the opposite muscle group) needs to relax. This is an example of how both Yin and Yang together are needed to create movement. In the spirit of Zhoudun Yi’s essay, Yang generates motion while Yin allows this to happen by countering with stillness. It’s not stillness in the true sense, it’s stillness in the context of motion, which is not quite the same thing. Remember, for a muscle to relax, a nerve signal is sent to the appropriate motor neuron that forces the muscle to relax, it’s called reciprocal inhibition. It’s an ACTIVE process!

Another example would be eccentric contraction. In this situation, an antagonistic group of muscles contract to slow down an initiating movement. For example when you throw a ball, the initiating agonist muscle group contracts to create the motion, while the eccentric antagonistic muscle group contracts to slow down and control the movement. Once again Yin is being used to balance out, or counteract, the Yang.

A third and final example can be seen in the case of muscle guarding. When you injure yourself, your body wants you to stop moving to protect the area. Pretty sensible thing for your body to want, right? It does this by contracting the muscles around the injured area, effectively stopping you from moving! In this example you can see that an active contraction (Yang) leads to an inability to move, or in other words, stillness (Yin).

And so, Taiji can in fact be used as a philosophical model to illustrate, in many ways, the dynamics of motion. A model that we can easily apply to our physical body.

So what does all this mean in terms of movement therapy? Good question. Clearly, movement therapy is a tried and tested medical intervention. It may be the oldest of all of them! Yet most Chinese Medicine practitioners don’t rely on movement as a primary clinical tool; they prefer acupuncture and herbs. The counter-argument here, of course, is that acupuncture or herbs might improve the potential for movement. This is true! But isn’t the best way to improve movement, well, to move? I’ve specialized in treating complex movement disorders for over a decade, and I can say with certainty that no movement disorder will improve unless movement plays a major part in the program.

Moving Is A Pretty Normal Thing To Do

Lets see what the Neijing, Suwen, Chapter 1 says about the importance of movement:

是以志闲而少欲,心安而不惧,形劳而不倦,气从以顺,各从其欲,皆得所愿。

Hence, the mind is relaxed with few desires, the heart is at peace with no fear. Work the body, but not to exhaustion, Qi will flow smoothly. According to such simple desires, wishes are easily achieved.

故合于道。所以能年皆度百岁,而动作不衰者,以其德全不危也。

So, they were one with the Dao. They were able to exceed a lifespan of one hundred years, their movements and activities did not weaken, their virtue was perfect, and they did not meet with danger.

What I like about these quotes is less what they specifically say and more what they imply. The Neijing points out that movement is just as important a consideration as are the mind and emotions. I know many practitioners that overemphasize the mental and emotional aspects of health, while ignoring the physical reality of the body. Don’t fall into that trap. A happy couch potato is still a couch potato.

Another quote from Neijing, Suwen, Chapter 13:

今世治病,毒药治其内,针石治其外,或愈或不愈,何也。

往古人居禽兽之闲,动作以避寒,阴居以避暑,内无眷慕之累,外无伸官之形,此恬憺之世,邪不能深入也。

When people of nowadays treat a disease, they employ herbs to treat the interior and needles and bian stones to treat the exterior. Some are healed while others are not. Why?

People in antiquity lived among the animals. They moved and were active and this way avoided the cold. They resided in the shade and this way avoided the summer heat. Internally, they were free from yearning; externally, they did not struggle for benefit or reputation. In such a peaceful and tranquil world, evils were unable to penetrate deeply.

Again, the same prescription. Essentially, chill out, move more, spend some time outside, don’t be a jerk. Maybe get a pet dog or something. The important takeaway here, in my opinion, is that a healthy lifestyle is more important than herbs or acupuncture, and a healthy lifestyle includes movement.

Dancing With Demons

Everybody knows movement is good for you, but now lets get more specific and look at movement in a clinical context.

Neijing, Lingshu, Chapter 42:

黄帝曰:余受九针于夫子,而私览于诸方,或有导引行气,乔摩、灸、熨、刺、焫、饮药之一者

Huang Di said: I have studied the nine needles from you, and self-studied many other perspectives. They include guiding and pulling, moving qi, massage, moxibustion, hot compresses, needling, fire needles, and medicated decoctions.

Here we are introduced to the actual movement therapeutics of Guiding and Pulling (Daoyin) and Moving Qi (Xingqi). These terms can be used separately, as in, there is Daoyin, and there is Xingqi. But they can also used together, as in Daoyin Xingqi.

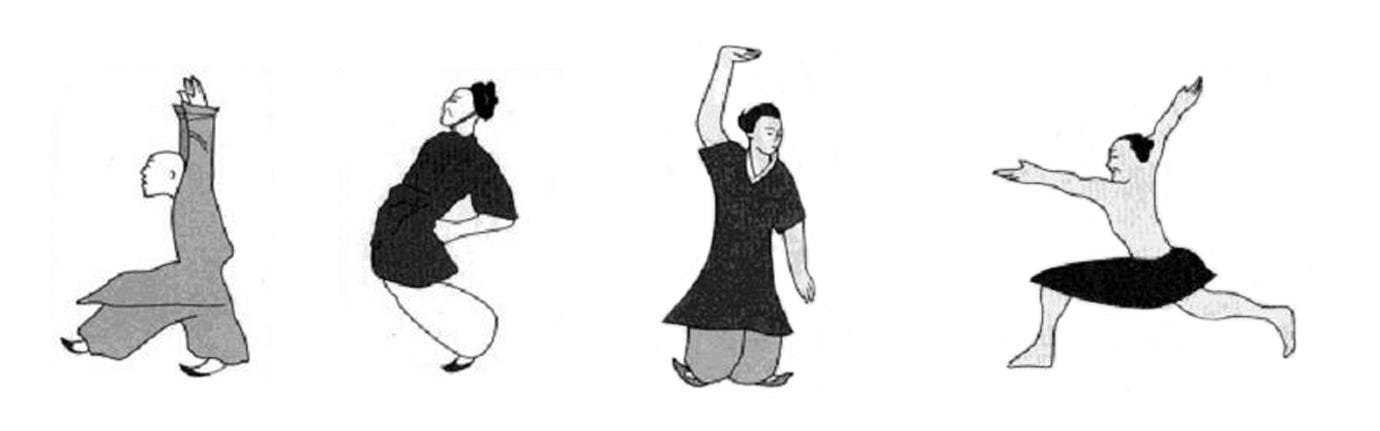

Dao Yin was popularized by a manuscript discovered in the Ma Wang Dui tombs, the Guiding and Pulling Chart (Dǎo yǐn tú 导引图). It illustrated 44 different positions that represented an early form of movement therapy/gymnastics. Some say it was more akin to spontaneous shamanic dancing meant to expel demons. (I sure wish I could dance away my demons.) Who knows, but either way, there’s a lot going on in those drawings. For example:

I think everyone would agree that these look like pretty straightforward stretchy-type movements. But then there are also these:

These are what I look like on the dance floor. Not sure what’s going on, the simple written descriptions included in the original manuscript might help to clarify, but I’m too lazy to read them. Then there’s this poor guy:

This looks more like the morning after too much wine and a lot of regret than it does a therapeutic exercise. Though admittedly, curling up into a little ball and pouting can be rather therapeutic at times.

The famous Daoist Chen Tuan (871 – 989 CE) created 24 Daoyin movements corresponding to the 24 solar terms. These are postures/movements performed at specific times throughout the year that help one adjust to the changing seasons. It has some really interesting exercises, like this one:

Not sure what to say about this one. Is he half horse? What’s wrong with his ribs? Is this some kind of nipple massage? So many questions.

As you can see, when it comes to these old illustrations, some make sense, some don’t. Many people have attempted to create specific movement sets based on them. A valiant effort, though one that inevitably leads to many assumptions.

Other popular sets of Daoyin exercises include 5 Animal Frolics (Wǔ Qín Xì 五禽戏) and the 8 Brocades (Bā Duàn Jǐn 八段锦 ). Daoyin is also discussed in the famous manuscript Book of Pulling (Yǐn Shù 引述). References for Daoyin are abundant.

Generally the complexity of these movements will vary. Some may be as simple as stretching your arms over your head, while others could involve complex postures or whole body twisting motions.

What about Xingqi?

Xingqi movements will undoubtedly be less physically demanding or choreographically complex, but will demand heightened attention in other areas, like breath control and sensory awareness. In the Neijing, the term Daoyin Xingqi is used together, but if we expand our search, we see that Xingqi is also used exclusively.

For example, a very old Daoist text, Biographies of Immortals (Liè Xiān Chuán 列仙传) states:

邛疏者,周封史也。能行气炼形。

Qiongshu ambassador in the Zhou dynasty, he could move [his] qi and refine [his] form.

Here we see Xingqi is complimented by the term Refining Form. Qi and Form is a common theme in traditional medical texts. A simple way to make sense of this is to associate Daoyin as affecting form, and Xingqi as affecting Qi. For clarity, Qi could be defined here as ‘activity' or ‘function’.

Of course, these two approaches overlap; one cannot fully exist without the other, but understanding the parts of the whole is a valuable perspective. From a modern perspective, form and Qi could be seen as anatomy (form) and physiology (Qi). If you want to discuss movement in particular, then form would be the muscle tissue while Qi would be the nerve impulses acting on that tissue.

In a practical light, Daoyin can be assessed as the effect of physical movement on tissues. There are five primary tissue categories in traditional Neijing theory, connective, bone, skin, muscle, and vessel. When you move, these tissues change. Connective tissues change shape and alignment as mechanical stresses move through them. Bone, under pressure, will become stronger, dense, and more structurally sound. Skin responds positively to activity by flushing itself and detoxifying the body. Muscle tissue under resistance fills out to maintain its mass. Exercise induces angiogenesis (new capillary sprouting) to maximize blood flow throughout the body.

Xingqi can be assessed as the effect of physical movement on the nervous system. Think of this as movement programming; essentially, how a person controls their movement. This is primarily done through sensory development. In movement language it is called proprioception, or the sense of self-movement, force, and body position. Xingqi also relates to other ‘invisible to the eye’ aspects of physiology, like breath, hormones, and cognition.

Couch Potatoes And The Earth Element

Daoyin Xingqi is a valuable clinical tool, if you know how to use it. The problem is that the extent of its application in most clinical settings is to simply recommend joining a generalized movement practice. For example, referring a client to a group Taiji Quan, Qigong, or Yoga class. Don’t get me wrong, these are great practices, but movement therapy should be prescriptive and specific, not standardized and generalized, if you want to apply it in a clinical setting.

The Neijing does give some specific advice in terms of prescribing Daoyin in Suwen Chapter 12:

中央者,其地平以湿,天地所以生万物也众,其民食杂而不劳,故其病多痿厥寒热,其治宜导引按蹻。

The centre region [Relating to the Earth Element], the land is flat and damp. It is here that the heavens and the earth produce many things. These people eat a diverse diet and they do not work much. So, they commonly suffer from atrophy and cold limbs, as well as cold and heat illnesses. Treatment should be with guiding & pulling and manual massage methods.

Let’s just cut to the chase here and point out the obvious. This paragraph is saying that people who eat too much and don’t exercise are obviously the ones who should clinically be prescribed Daoyin Xingqi. Of course, outside the clinical application, many of these practices are preventative and, if engaged in regularly, can offset negative aspects of aging. This is where the generalized practice routines come in handy. But what about the clinic? How does one apply them in a prescription model?

Treating Couch Potato Syndrome

Daoyin Xingqi is not just about your physical body, it relates to your physiology as a whole. In this sense, it can be used to treat more than just orthopedic conditions.

Of course, applying Daoyin Xingqi type movement prescription to treat a Chinese medicine diagnosis is a little tricky. What movements are good for Liver Qi Stagnation, or Dampness in the Spleen? How can movement improve Rebellious Qi Patterns or Cold Patterns or a Deficiency of Yin?

It’s important to remember that, for the most part, movement directly affects the tissues of the body while indirectly affecting the physiology of the body. What that means is that any benefit to your heart, liver, digestion, allergies, headaches, constipation, mood swings, or insomnia, will be secondary and indirect to the physical movement itself.

For example, movement can massage and stimulate organs, warm tissues, promote blood flow, stimulate hormone production, clear inflammation, and promote tissue growth. But without movement these things will not happen. Selecting the appropriate movement, the approach to performing the movement, the duration of the movement, and of course evolution of the movement, is key.

I know what you’re thinking right now. You’re thinking…

“You tea-drunk rambling fool, hurry up and give me the goods!! How do I use this stuff in the clinic?!”

Sorry, but it’s not that easy. Let me flip the script on you. Where is this information? Why is movement prescription not as applied a clinical module as is acupuncture, herbs, moxibustion, massage or diet? Why is the movement portion of Chinese medicine only administered as a generalized health maintenance movement practice recommendation, and not as a specialized clinical prescription?

Relax, don’t be so dramatic. Here is a valuable resource to start you off by PhD researcher Dolly Yang, who has written a few worthwhile papers on the topic (warning, it’s very long).

And here is another great resource, a translation of the Book of Pulling (Yǐn Shù 引述) by Vivienni Lo. Enjoy!

Don’t Be A Couch Potato Therapist

There’s a lot in this article to stew over. If anything, my intension (as well as maintaining my reputation of being a bit of a jerk at times), is that it acts as a call to action for Chinese Medicine therapists to think more about movement as a specialized therapeutic module. Years specializing in movement-focused neuro-rehab has given me a solid perspective on the value traditional physiology and movement practice models have in the clinic. A background in physiotherapy, personal training, kinesiology, or any other movement specialty, is a step in the right direction, but not essential. Chinese medicine embodies a very rich historical encyclopedia of movement ideas.

So, don’t be a couch potato therapist. Turn off the TV, and start moving.

What would a whopper of a ‘leave you hanging’ article like this be without a proper deliverable! Yes, I’m putting together a live Chinese medicine therapeutic movement workshop. I’ll keep you posted.